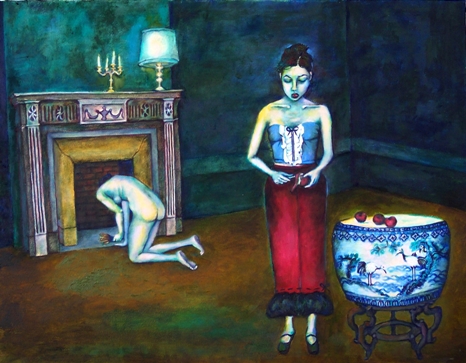

Mood:

This is the final part of the essay that will be published in Schizophrenia Bulletin. The beginning of the essay is in the previous blog entry. As part of the legal agreement I signed I can publish it in it's pre-print form on my personal website. Eventually this essay will be published on my main website, schizophreniaandart.com. Now that the publishing bug has bitten, I'm thinking of writing an essay for Schizophrenia Bulletin titled "Portrait of a Marriage" about what it is like to have a person with a mental illness married to a person who doesn't have a mental illness.

Ability and Disability, Part II

A small gallery owner and I once had a friendly acquaintance that lasted several years. He professionally framed several of my painted canvasses. When I visited him in his shop I was always at my most attractive. Showered, rested, and a paying customer. The new car I parked in his lot had been bought for me by my husband. This man couldn't "see" anything wrong with me. My creeping rate of artistic production baffled him. And I think he was curious about my new marriage, why would a man willingly take an unemployed, sick woman as a wife?

One day he said to me, "You have a nice personality. You would interview very well. Why can't you get a job at the kennel down the road?" What the gallery owner hoped to do was to prove my status of being disabled wrong. His theory that I was strong enough to become a contributing member of society, earning a wage, was intended as a compliment. In an attempt to find a normal place in the world for me he had thought of a menial job that required no education and minimal intellect. What I would be doing at the kennel was vague, but the implication was that I should clean up after caged animals. The intent was to prove that my psychiatric disability could be overcome by simply finding the right task for me to do. He imagined that a job that was purely physical, washing excrement off concrete floors, wouldn’t tax my brain or invoke the disability of schizophrenia.

Perhaps for several hours every day I could use my best hours of clear thought and concentration working at a kennel. Here my acquaintance was also challenging my resolve for recovery. If I declined to apply for such a job then the fault must lie with me and my personal values and not my illness. But the assumption that physical labor somehow bypasses my thought disorder is incorrect. In my world of pennies and necessary cost, the act of directing my body in coordinated movement is just as mentally fatiguing as sitting in front of a computer and typing. Bending language, as I have done in this essay, and bending my body are two very different tasks but they both involve my person as a whole.

A good friend once said to me, “Karen, you become the book you read.” It often seems that my mind is like a light switch that can only be turned on or off and it is seldom able to roam in-between. Sometimes I wonder if the main feature of my illness isn’t just an abnormal intensity of experience. I am too much in the world, concerned with the world, and consumed by the world. In my household I am the slowest dishwasher and the slowest with the vacuum cleaner and the dust rag. However, I am also the best dishwasher and the most thorough cleaner of every nook and cranny. One might say that I take life, and everything in it, too seriously. But to be more accurate, perhaps I burn out so fast because I am not splintered into parts, lacking the agile ability to project or withhold concentration. My existence isn’t filtered out into more important or less important parts, and so, I am vulnerable to life’s abundance of stimuli.

My choice is to use what limited mental power I have to the utmost. I have chosen a career in making art because I find painting to be a joyous wedding between the concrete and tactile and the abstract and intellectual. As if I were conducting a musical symphony, when I work all parts of my brain are engaged, connected, and coordinated. There is nothing, ever, boring about making art. Technical problems concerning color, shape and the painted surface are very real to me, and the adventure to solve them is exhilarating. Some of the pictorial mysteries I’m involved in, by studying what other artists have done, will take years to unravel. Don’t many people secretly dream that they could one day find work that they feel passionate about? The balance of my life is fair and good because in the midst of disability I have found moments of ability that are sought after, cherished, and repeated from one day to the next.

Sometimes I go really slow and careful through the day. I have to do whatever I can to push myself forward and not give in to despair.

Sometimes I go really slow and careful through the day. I have to do whatever I can to push myself forward and not give in to despair.